Celebrating women artists, activists, writers, performers, community groups and organisations, with a diverse programme of…

How Art Can Give Voice to the Medically Unexplained

Jamila Prowse surveys how artists, writers and critics become their own unofficial biographers when grappling with illness and misdiagnosis

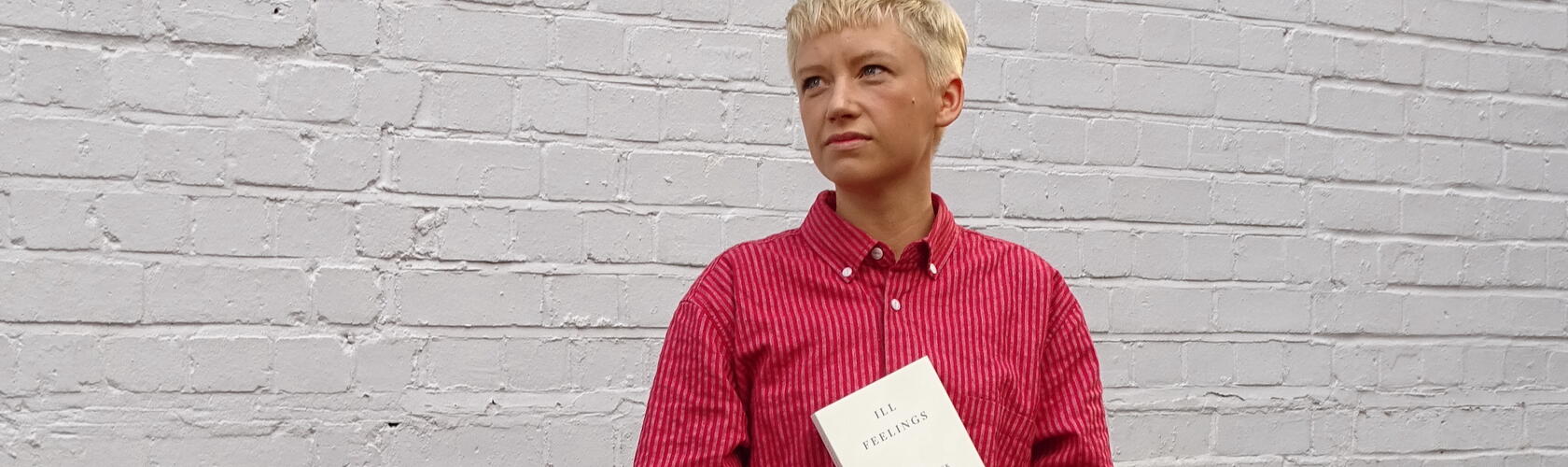

On the day I was meant to write this piece, I had an unexpected phone consultation with Personal Independence Payment, the UK’s disability benefit service. Nearly four months after initially submitting my application, I found myself once again having to supply evidence of the disability for which I do not yet have a concrete name. In Ill Feelings (2021), Alice Hattrick animates how, as disabled and chronically ill people, we have become our own unofficial biographers. The author stitches together their medical history and that of their mother alongside written testimonies of numerous women who have done the same – including Louise Bourgeois, Florence Nightingale and Virginia Woolf. In 1995, Hattrick’s mother collapsed with pneumonia, from which she never fully recovered, leading to her later being diagnosed with ME, or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome; Hattrick meanwhile began to experience symptoms that mirrored their mother’s, initiating an ongoing battle to get doctors to take Hattrick’s own illness seriously.

Hattrick illuminates the process of accumulating proof that you are ill – for medical practitioners as much as for yourself – to push against malpractices of medical gaslighting: ‘When my mother and I enter the doctor’s surgery, our symptoms are still opaque and illegible, real and unreal, they are still ours alone to record and, often, self-medicate.’ Even in the case of a formal diagnosis, chronic illnesses are commonly unexplained: there is no clear rationale or catalyst as to why they started and we are routinely doubted as to the veracity of our ‘ill feelings’.

It wasn’t until I started trying to give a name to the difficulties I’ve had since childhood, that I realized how commonplace the struggle to get an ‘official’ diagnosis is. In Leah Clements’s short story ‘Diagnosis’ (2020), commissioned by Chisenhale Gallery, she considers the power of being able to give a name to something. When Clements was a child, she stood up too fast and began to feel dizzy and faint; she describes how her dad taught her the word ‘head-rush’ to describe the experience. Now, Clements feels sensations that change and evolve; sometimes akin to growing pains, although she has stopped growing. She writes: ‘I think something’s wrong, but I don’t know how to say it and I can’t make anyone get it.’

Within disabled communities, diagnosis is not always a goal or conclusion; there is a pattern of self-diagnosis or, indeed, of not finding comfort in a diagnosis – formal or otherwise. This may, in part, be due to the number of conflicting diagnoses one person might receive over the course of their lifetime. Still, there are some significant benefits a diagnosis might offer, namely receiving treatment for your condition, access adjustments within the workplace and financial support. Though with ongoing cuts to disability benefits in the UK and a lack of research into many chronic illnesses, neither is a given.

Now, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to unfold, alongside the 4.9 million people who contracted the virus and tragically didn’t recover, there is a generation living with unexplained illnesses under the blanket term Long COVID. Gabrielle de la Puente, co-founder with Zarina Muhammad of online writing platform The White Pube, is one such person. After catching COVID-19 towards the start of the pandemic, De la Puente continues to live with a multitude of shifting symptoms. In an episode of The White Pube’s podcast devoted to Long COVID, De la Puente reflects on the uncertainty of an illness that is constantly changing and how to communicate that publicly. ‘There’s something about the visibility [that] just makes me feel self-conscious because there are days when I can do stuff and days when I can’t. I don’t want people to think: “Oh, she’s back to normal now.” And then to think that I’ve lied about any of it.’

So, where does that leave us? Where can we retreat to in the wide expanse of unknowing? Well, in many ways, into the solace of each other’s arms – strangers-made-friends on the internet – or another person’s words printed in black and white in a bound book. When Hattrick’s mum read the manuscript of Ill Feelings, she described it as ‘a letter you have written to me’. De la Puente and Muhammad, after years of friendship, cry on the podcast and, in their words, ‘sit in that puddle together’. If undiagnosis and misdiagnosis can feel restrictive, collectivity is the sweeping antithesis. Shared experience might not soften the pain but, at the very least, it tells us we are not alone.

This Post Has 0 Comments